Our Numbers Speak for Nature.

Our Numbers Protect Nature.

Our Numbers Connect People with Nature.

Learn more about our history using #NumbersForNature below.

Conservation Strategy Fund is an international non-profit organization that provides strategic insights, information, and tools to fuel sustainable development. We use the power of economics to support environmental conservation by integrating the economic value of natural resources and human well-being into development decisions.

For more than 25 years we have been using #NumbersForNature to understand the true costs and benefits of human economic activities on environmental and social well-being.

Journey through those 25 years with us and learn about our groundbreaking research, economic tools, and successful conservation strategies.

Our History

Maya Forest in Mexico

2009

Is marine conservation a good deal?

The value of a protected reef in Belize.

Coral reefs provide a variety of benefits to people, and their protection can be an attractive public investment. The first step in determining whether such protection makes economic sense is to measure the goods and services flowing from the reef ecosystem. In 2007, CSF led a comprehensive account of the ecosystem services provided by a reef in Belize to help policy-makers better understand the economic potential of reef systems.

We released a valuation study for the Gladden Spit and Silk Cayes (GSSC) Marine Protected Area in Belize and estimated the total use value for the GSSC Marine Reserve in Belize at approximately 1.25 million USD per year. If we include the value of the site to Belizeans who live nearby who visit the area for recreational or aesthetic purposes, the monetary value of the reef rises to 4.5 million USD per year. Our findings suggest that further investment in MPAs like this one are likely to have an attractive return.

Management expenditures of 315,000 USD for 2007 helped to secure net annual benefits of at least 4 million USD.

Jalapão, Brazil

Story From the Field

Wild

Chocolate

In 2011, CSF’s Malky discovered a complex, but promising web of connections between economics, the environment, and the human condition when he created a market study for Bolivian chocolate company Selva Cacao (“Jungle Chocolate”).

This story starts millions of years ago with the emergence of the cacao tree in South America’s rainforests. It was domesticated thousands of years ago and is now grown in vast plantations throughout the tropics. The stuff Selva Cacao uses, however, is still from wild trees in the Amazon Basin of Bolivia.

The company asked CSF to analyze the economic feasibility of employing indigenous forest populations to harvest wild cacao (“cacao” is a synonym for “cocoa”) and then make it into commercially viable chocolate bars. Malky began to ask questions. What were the benefits of wild cacao? What would villagers think of this opportunity? What makes for popular chocolate?

He discovered that harvesting wild cacao had multiple benefits. The bean grew without farmers having to resort to deforestation, soil abuse, or the use of pesticides. Malky and other researchers also learned that villagers in communities like Carmen del Emero already knew how to collect the wild cacao beans. CSF proposed that Selva incentivize its potential workforce with a revenue-sharing model in which ten percent of all chocolate sales would go to the households involved in gathering wild cacao. Not only would the plan put extra money in people’s pockets — it would keep villagers from doing other work that might involve deforestation.

Then there was the matter of taste.

“We hosted focus groups, and people tried the wild chocolate side-by-side with products many considered some of the best chocolates on the market,” says Malky, describing the blind tests he ran. “The wild chocolate was always chosen first or second.”

Malky found that in the La Paz market brand loyalty was weak. Believing that there was room for a distinct (and only slightly more expensive) newcomer, he projected that Selva could sell 30,000 bars per month.

Years later Malky sees Selva’s rainforest-sourced chocolate in stores all over town. He knows it’s still a small business, but the chocolate bridge it built to the rainforest makes a real difference to people and their ability to continue to coexist with the forest.

Andes Mountains

2016

BUILD project from CSF and USAID concludes.

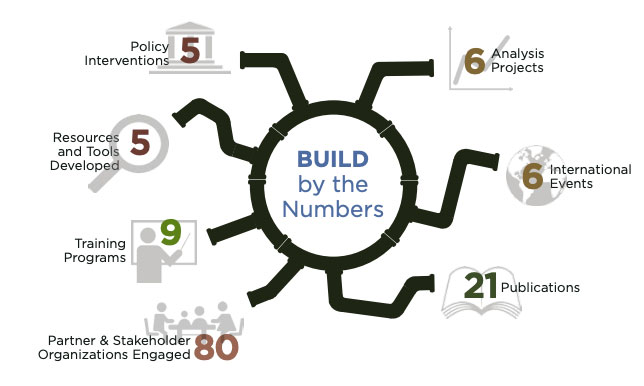

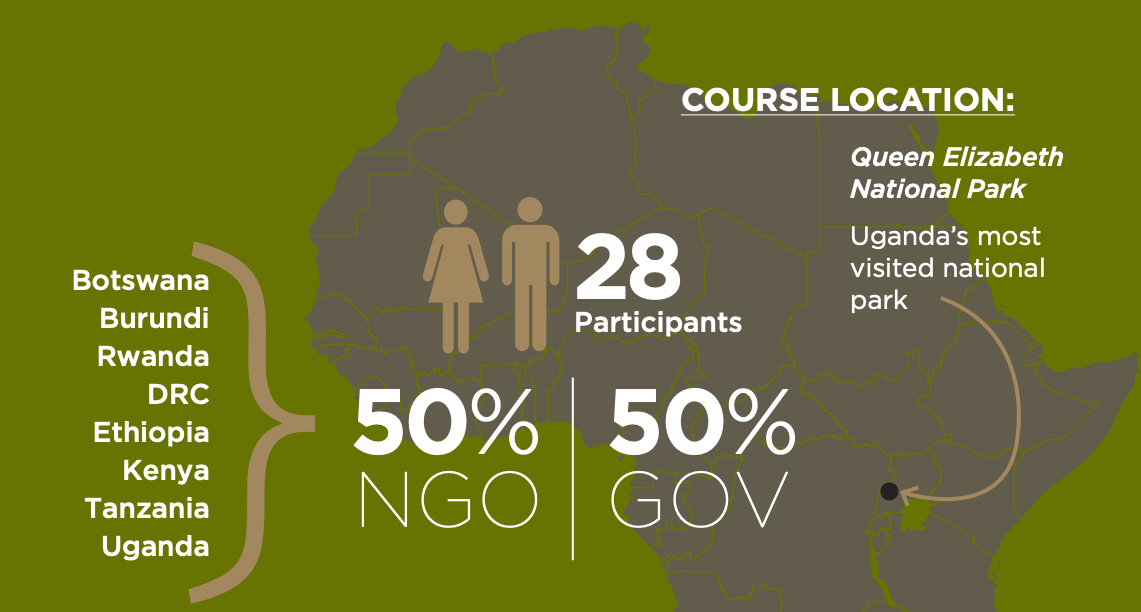

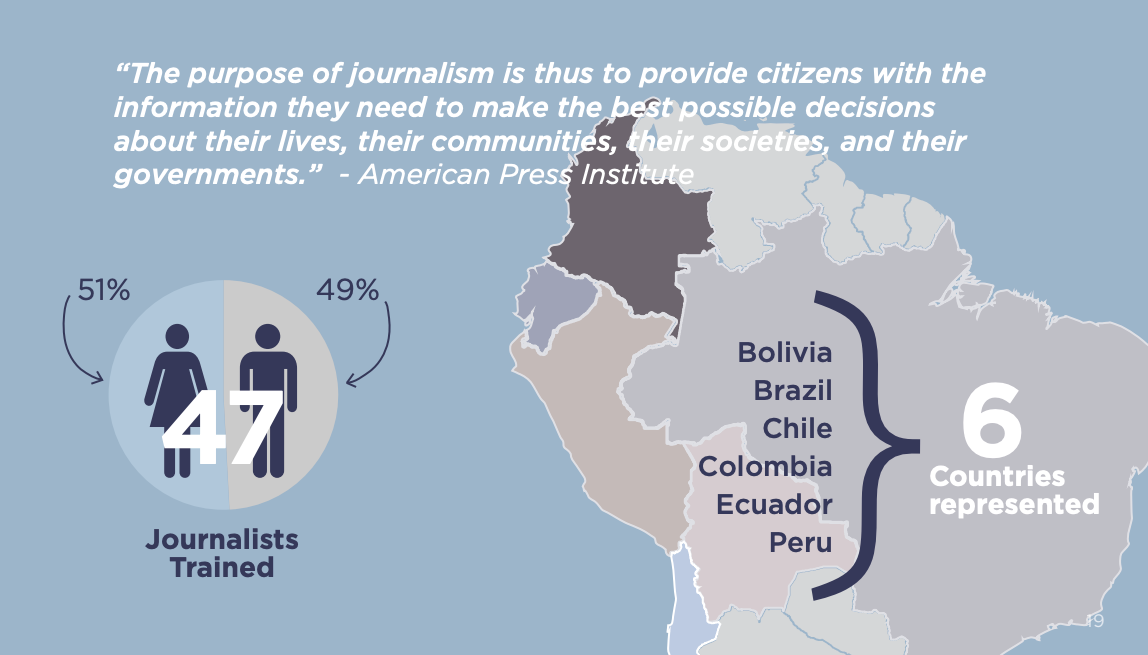

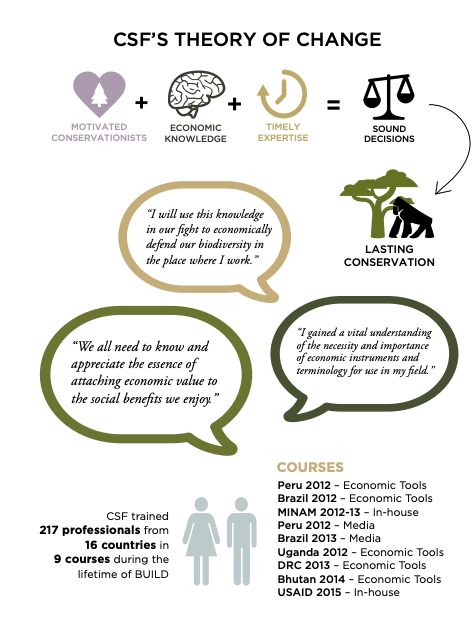

Our Biodiversity Understanding in Infrastructure and Landscape Development (BUILD) report covers four years of our success using economics to influence infrastructure development in support of biodiversity conservation.

CSF trained 217 professionals from 16 countries in 9 courses during the lifetime of BUILD

Our environmental impact analysis work halts or stalls 6 development projects, protecting people from displacement and reducing nearly 96000 hectares of deforestation.

2021

CSF publishes landmark Mining Impacts Calculator in Brazil to reduce illegal mining activities and conserve the Amazon rainforest

In the Amazon, a lack of data and evidence-based information on the socio-environmental costs of illegal artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) limits a country’s ability to regulate mining activities and safeguard communities from the environmental threats of ASGM.

In 2021, CSF developed a Mining Impacts Calculator that provides instant calculations of damages expressed in monetary values for different ASGM infractions using information on gold mining type and important contextual characteristics. This calculator is based on economic valuation methods for calculating environmental and social damages.

Our goal for the calculator is to provide information and awareness of these impacts so that government agents and civil society can strengthen their work against illegal gold mining and ensure people’s right to live in a safe and healthy environment. To tackle ASGM impacts at scale and promote sustainable regional solutions, it quickly became apparent this tool could be immensely useful in other countries in the Amazon and CSF has now expanded this tool to cover mining activities in Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Guyana and Suriname.